What is a translation memory? We explain the workings of one of the translator’s most important tools

Most of the people reading this post will probably have translated a text from scratch at one time or another, without using Google Translate or similar software and without using any professional tools. Perhaps there are some who think that, in the absence of machine translation, this is how professional translators work: translating word by word and looking up any queries in the dictionary, labouring over each sentence from beginning to end. However, that is not the case, even back in the days when CAT (computer-assisted translation) tools, translation memories and other technological aids did not exist.

Firstly, translators have always worked by treating the text to be translated as a unified whole, in order to gain an understanding of its content, tone, style and context. This enables them to obtain a complete unit of meaning and avoid the pitfall of literal translation, which is what tends to happen when a text is translated word by word and, as a result, fails to communicate the true meaning of the original. Translators would use their language skills to carry out the translation, revising and proofreading their work and consulting reference sources where necessary. If they had any queries, they submitted them to the relevant experts on the subject matter in question.

It was after the introduction of translation-assistance software that the working method evolved to place even greater emphasis on context, consistency and quality. In this post we explain what a translation memory is, and how it is one of the many tools that have enabled these advances to be made.

What is a translation memory?

If we imagine a translator prior to the generalised use of computers, we might picture someone using a notebook or card file to make notes of tricky sentences they had translated, phrases that recur in a particular type of document or sector, or specialist terminology. These notes were the precursor to today’s translation memories and terminology glossaries.

A translation memory is a database that stores the respective translations of the different segments into which a text has been divided (complete sentences or paragraphs, phrases, etc.). When there is a new text to be translated that is similar to previous ones, the task can be significantly streamlined without negatively impacting the quality, consistency and contextualisation provided by the process of human translation, given that, ultimately, the translations stored in the database were originally created by a human.

Thus, translation memories form part of a broader set of translation-assistance tools that enable texts to be broken down into segments and translated, and then allow translators to retrieve the translated text in the form of pairs of segments. These pairs are referred to as translation units (TU), and comprise the text in the original language (source) and the translated text (target). This set of tools may also contain terminology glossaries, etc.

Translation memories can have different origins: they may be created by the CAT tools themselves, or derive from external databases that have been incorporated into these tools (this is common with large companies that have worked with more than one translation or content-creation agency that shared the same translation memory).

The advantages of translation memories

These tools not only offer the advantage of efficiency, when translating new texts that coincide, in full or in part, with earlier ones; they also make it possible to ensure greater consistency of style, terminology and tone in texts by the same author or related to the same sector, and in general help to improve the quality of the translation.

- They streamline the translation process and enable faster delivery, as certain texts may only differ from each other in terms of their figures, punctuation, proper nouns, etc.

- They make translations cheaper by streamlining the work of the translator, who does not need to invest as much time in each translation.

- They improve the quality of translations by preventing inconsistencies, even in longer texts and in cases where various translators are working on the same document.

Which types of document benefit most from the use of a translation memory?

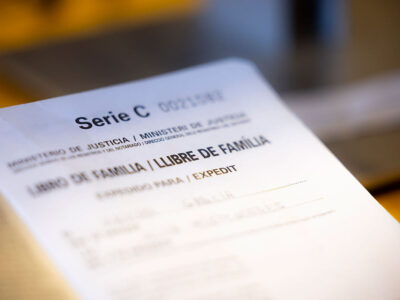

There are documents whose content, by virtue of its nature, differs substantially from that of earlier texts. Examples include court rulings, creative and advertising content, personal communications, original works of literature, unpublished scientific research, etc. However, there are many other types of document where patterns of repetition can be found. These include:

- Standardised legal and financial documents, etc.

- Standardised technical and medical documents (user manuals, patents, blueprints, warranties, patient information leaflets, legal forms, etc.).

- Online content (product files, privacy policies, terms and conditions of sale, etc.).

- General texts from the same company or organisation that use the same or similar expressions and content on their websites and in their product manuals, advertising materials, etc.

How translation memories differ from machine translation tools

After reading our explanation of how translation memories work, you might think that they are related to machine translation software, such as Google Translate. However, they are in fact very different. Let’s start with the fundamentals: machine translation uses algorithms and mathematical models to translate text from one language to another. It is not based on an initial translation, created by a human, which can subsequently be retrieved and used to translate texts that are similar.

How does a translation memory work, on a step-by-step basis?

As we have explained, a translation memory is a database that stores segments of translated text (in both the source and target languages) from previous projects. The translation process begins by setting in motion a series of CAT tools, as detailed below.

1. Dividing the text into segments

The text to be translated is uploaded into the program. The software then divides the text into the segments we described above (complete sentences or paragraphs, phrases, etc.). The different CAT tools available on the market do this in different ways, and the process can be adjusted in line with the translator’s requirements. In general, the segmentation is carried out based on the text’s punctuation (full stops, colons, etc.) or other file markers (line breaks, tabs, tags, etc.).

2. Searching for matches

For each segment, the translation memory searches the database for matches, which can be full or partial. The closeness of the match is expressed in the form of a percentage.

Thus, we may find segments that are exactly the same as those translated on previous occasions (exact matches), or are sufficiently similar to serve as a basis for the translation of the new segment (“fuzzy” matches). If the document is found to contain similar or identical content to an earlier translation, the client can be offered a discount and given a lower quote.

3. Suggesting translations

The program will suggest translations for each segment, in accordance with the information stored in its database. The translator can accept, reject or modify the suggested translation.

If the suggested translation is suitable for the context of the document being translated, the translator can approve it as it stands. However, if the translator believes that the translation can be improved, they can modify the suggested text.

Once the segment has been translated and the translation confirmed, it is stored in the translation memory, ready to be used for future translations.

Ampersand uses professional translators and the most advanced CAT tools

At Ampersand we work with a wide variety of translation memories, ranging from those we create ourselves for SMEs, to databases that are provided to us by multinational corporations. Additionally, we have strict procedures in place to ensure they are kept up to date and functional. Where necessary, we consult with our clients to achieve this. As a result, we are able to streamline our processes and offer optimum quality at the best price.