What is the Apostille of The Hague? Countries and documents where it is required and more

If you have reached this post, it is likely that you have not found sufficient or sufficiently clear information on what the Apostille of The Hague is. This could be due to the fact that, when legalising official documents from other countries, it is often but not always a requirement, which creates confusion. Do you always need an Apostille for a document to be valid in another country? Or only for some countries? And if only for some countries, do you need it for every document? What exactly is the Apostille of The Hague? We’ll try to answer all these questions.

A procedure to simplify legalisation

Public documents, such as birth certificates, academic diplomas, criminal records or powers of attorney, are issued by a country’s responsible authority and are legally valid within that country. However, if you want to use them abroad in order to, for example, claim an inheritance, sign a divorce agreement involving children or enrol at university, you might be required to legalise these documents so that they may be recognised as authentic and valid in your host country.

Before The Hague Convention of 1961 came into force, the legalisation of documents required several steps which could be long and costly, as they involved several parties: the consulate, a notary public in the issuing country and a notary public in the host country. Through the convention, signatory countries unified and simplified this procedure, creating an Apostille to give documents validity. An apostille is literally a note on the margin, and the term was already used to describe comments on or interpretations of texts. In this case, the Apostille of The Hague certifies the authenticity of the signature on public documents issued by a signatory country.

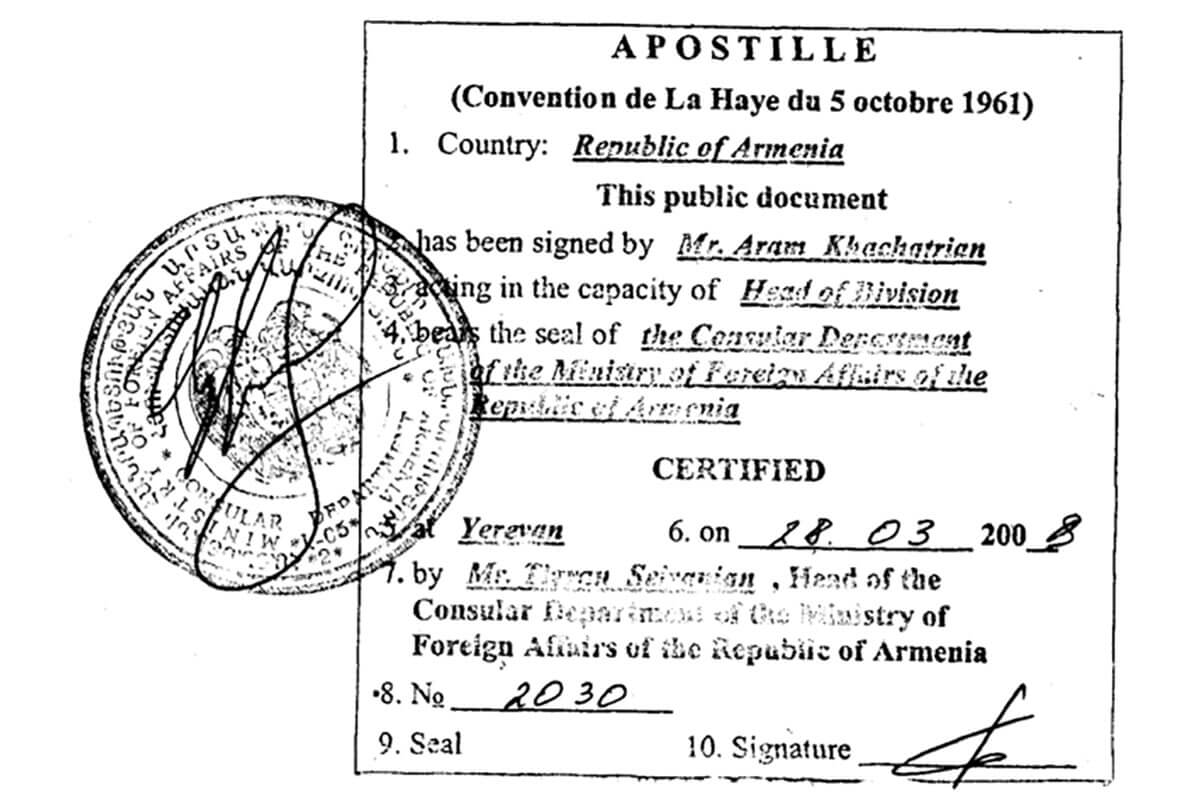

The Apostille includes data such as the issuing country, the name and position of the signatory, the stamp of the administration on behalf of which it was issued, a serial number, a date and a signature.

Signatory countries of the Convention of The Hague

Among the signatory countries of the Convention of The Hague are all Member States of the European Union, Andorra, Australia, Brazil, India, Japan, Morocco, Norway, Russia, Switzerland, Turkey, Ukraine, the United Kingdom and the United States, among others. You can find the complete list here, last updated in 2021.

It is valid for 124 of the 195 recognised countries in the world, although some countries with which Spain maintains frequent relations, such as Canada or Pakistan, require specific legalisation procedures.

Legalisation without Apostille of The Hague

For documents issued by countries which have not signed the Convention of The Hague to have legal effect in another country (or vice versa), a process called “diplomatic channel” – similar to the pre-1961 procedure mentioned above – is required.

For example, for Canadian documents the process may vary depending on the issuing province. The Spanish embassy in Ottawa can directly legalise documents issued in that city; however, for all other cases you should get in touch with the Spanish consulates in Toronto and Montreal to request information. In addition, the legalisation procedure may change depending on document type (academic record vs diploma; university diploma vs non-university diploma, etc.).

How to find out which legalisation procedure to follow in each case?

It is very difficult to know beforehand what kind of legalisation each document requires. As we have noted, even in the case of signatory countries, certain documents require an Apostille while for others a sworn translation is enough.

In any case, only public documents issued by public administrations (registry, tax agency, social security, etc), educational institutions (university, school, etc.) or a notary or attorney (depending on the country), among others, can bear an Apostille. Private documents (a contract between two companies, an insurance policy, etc.) must be certified by a notary public so that they become public documents. This subsequently allows them to carry an Apostille. Documents issued by civil servants or consular workers needn’t carry an Apostille because, as stated above, they already have sufficient authority for the document to be considered valid.

Nevertheless, it is the institution where you wish to present the document which must state which requirements it applies when accepting a document’s validity. For instance, if you need the document to enrol at university, you should ask the university what procedure you should follow. If you need it to claim inheritance, your lawyer should obtain the information needed from the authorities of the country where you will be making the claim.

Translation of the Apostille and Apostilled Documents

We have explained that the Apostille grants validity to the signature appearing on the original document. However, the country where you wish to present the document may have additional requirements, especially if a different language is spoken there. That is why you often require a translation of the document bearing the Apostille. In most countries, this must be done by a sworn translator. However, in this case also, all depends on the document required, the procedure you wish to complete and the institution which requires it. Moreover, sometimes a translation of the Apostille itself may be required. That is why it is common practice to translate the Apostille just in case; it is very short and barely affects the price of the translation. Translation of official documents is not required for countries where the same language is spoken, e.g., Spain and most of Latin America.

It is important to stress that the Apostille does not certify the authenticity of the translation, but of the original document. The authenticity of the translation is certified by the sworn translator, which can do so because they have passed the exams required by the relevant authorities.

Therefore, the full process is as follows:

- First, get an Apostille for the original document from the issuing country.

- Second, get the original document (usually including the Apostille) translated by a sworn translator.

- Finally, the translator stamps the document to certify the authenticity of the translated document.

Where to get the Apostille

In Spain, you can get the Apostille of The Hague in person from the Ministry of Justice and its territorial delegations by filling in an application form. In the case of documents issued by a notary public, you must request the Apostille from the Notary Public Association of which the notary is a member. The procedure may vary in other countries. Here are some examples: in the United Kingdom, the only authority which may issue Apostilles is the UK Foreign, Commonwealth & Development Office, while in Germany rules change from state to state.

Where can I get a document bearing an Apostille translated?

Getting the document translated by a translation company with good references is the best way to get a good sworn translation, since the company itself guarantees that all the requirements needed for the document to be accepted are met. At Ampersand, we have over 25 years’ experience, and we have translated thousands of documents into over 60 language combinations so they may be used all over the world.

Image credits:

Author: Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Armenia. Year: 2008. Title: Apostille Armenia. Image type: PNG. Retrieved from: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Apostille_Armenia.png